Landlocked land

Over a quarter of Māori whenua is landlocked. Landlocked land is land that does not have reasonable access to it. For instance, it is surrounded by other blocks and has no road, driveway or easement leading to it. Most Māori landlocked land is surrounded in part or whole by Crown land. In some cases, while there is theoretical access across this public land, it is not practical to traverse or it is accessible only for walkers who are able to undertake a long tramp. These land blocks are often isolated, extremely steep and rugged.

This landlocked land is a longstanding and fraught issue. It came about as millions of hectares of land were confiscated, compulsorily acquired and purchased in dubious legal circumstances. The small amounts of Māori land that remained following this are often cut off, isolated and landlocked. The history that led to the creation of these landlocked blocks is a story of significant injustice and a bitter insult to tangata whenua.

For tangata whenua, there is still no easy solution to the problem.

Te Ture Whenua Act covers 1.4 million hectares of land, so the 30 percent of that land that Te Puni Kokiri describes as landlocked adds up to over 1 percent of New Zealand – equivalent to cutting off access to all of Christchurch.

The adjoining land can be of a range of types, including public conservation land, freehold, crown forest, and involve unformed legal road. It also usually involves challenging terrain. For many landholders of landlocked land, helicopters are their only viable access.

Getting a court order granting access to the landlocked land

The law that deals with Māori Landlocked land is Te Ture Whenua Māori Act 1993 (s326A to 326D). This gives the owners of landlocked land the option to apply at any time to the Māori Land Court for an order granting reasonable access to the landlocked land. Unfortunately, as the Māori Land Court notes:

“… this is a long process, and you may be required to pay compensation for access across private land.”

The Court’s critical legal consideration is that the access should be reasonable.

Law Firm McCaw Lewis has a valuable article summarising what is involved when owners seek access to their land. It highlights the factors the Court must consider when it gives an order for access. These include what access existed when the land was acquired, how the land became landlocked, how the people involved behaved, the hardship that granting or not access would cause to the various parties, and other factors the court considers relevant.

If owners or occupiers of landlocked land are not entitled to an order under Te Ture Whenua Act they can apply for an order under the Property Law Act 2007 (ss327-331). The same barriers await landholders – the process can be slow, and it is likely that they will pay the costs of giving effect to an order for reasonable access.

As well as court costs, landholders can expect to face the cost of surveying, compensation, fencing and road construction. Even creating foot access can be costly and complicated. These costs can be a burden if the land in question does not provide a financial income, as is the case with a lot of landlocked Māori land.

Typically, there are more barriers than just the law. If land is landlocked it almost definitely is not productive land and does not have a formal trust managing it. Because of this owners will often lack the money and resources to even begin to unlock it. Sometimes some of the owners are unaware they own the property or they have passed away. This creates a barrier to unlocking the land before owners can consider a legal solution.

Herenga ā Nuku’s role

Herenga ā Nuku would typically only get involved in this legal process if the access sought was public access rather than access for the owners of the landlocked land. That is because the Walking Access Act 2008 aims to provide the New Zealand public with free, certain, enduring, and practical walking access to the outdoors.

We are not legally empowered to support landholders with private access to their land unless they also seek public access. We could become involved if we were investigating or preserving some aspect of public access. Our legislation also has no coercive powers to compel landholders to provide public access.

Herenga ā Nuku can help negotiate with adjoining landholders, as we do in our other everyday work.

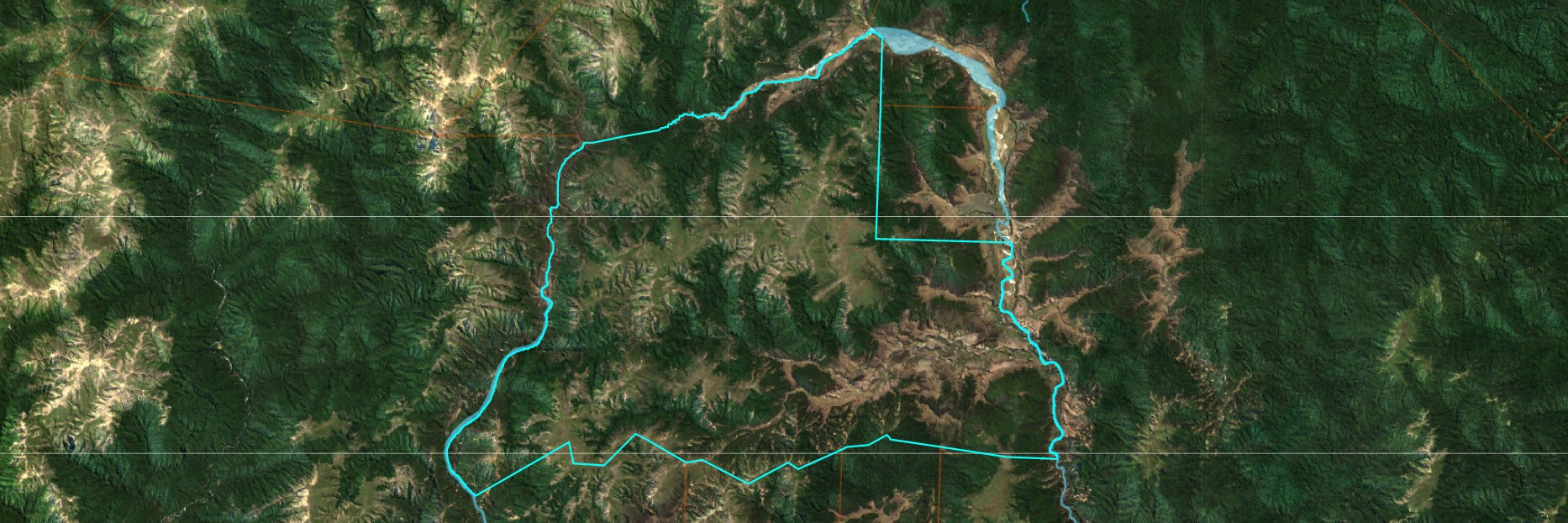

Our digital maps can also provide helpful background information about the boundaries to property parcels and any surrounding public access such as unformed legal roads, easements, esplanade strips and reserves.

Contact Herenga ā Nuku for advice

Herenga ā Nuku has a legislative focus on public access, this has not excluded negotiating and supporting exclusive Māori access. We understand the challenge that landlocked landholders face and we are flexible. In the past, we have successfully negotiated access for Ngāti Kahungunu to traditional sites over the privately-owned Cape Kidnappers Station.

Herenga ā Nuku has previously offered landholders of landlocked land maps and 3D images identifying public foot tracks and other potential access solutions.

Other options

Herenga ā Nuku offers useful advice and support, but it cannot offer comprehensive help with Māori landlocked land. Other Crown agencies are also unable to solve the whole problem. There are few existing mechanisms to right the wrong, let alone resources to enable those mechanisms.

There have been overseas investment cases where there may have been an opportunity to provide access to land-locked Māori blocks, but this is not a criterion the Overseas Investment Office applies to consent conditions.

If the adjoining landowner does not want to negotiate or allow access to the landlocked land, the options are limited, expensive, and legally fraught. Aside from seeking an order from the Māori Land Court, there are two broad options:

1. Purchase land or access

The first option is buying access to the land either by purchasing adjoining land or rights to access across that adjoining land in a willing buyer, willing seller scenario. This could involve buying the adjoining block, establishing an easement, and then on-selling the land or purchasing or leasing an access route. This option is only available for freehold land, and it is a costly solution. It also raises questions about who will maintain and manage the access.

Herenga ā Nuku’s position has long been that public access is a public good that we prefer people to grant out of goodwill rather than to make a profit. This is particularly true where the landlocked land is cut off in part or whole by publicly owned land.

2. Compulsory acquisition

A second option is the Crown can acquire the land under the Public Works Act 1981. Again, this is a complex, multi-agency process and can be costly. Providing access to landlocked blocks for the sole benefit of the landholders is unlikely to meet the definition of ‘public work’, which means, in most cases, that the Public Works Act is not the right legislation to address the problem.

Conclusion

The ability to unlock land through Te Ture Whenua Act provides a legal pathway for landlocked Māori landholders. But in practice, the problem remains. The law can be a costly and time-consuming process, and there is little or no practical support for landowners to address the financial and resource barriers that prevent them from going to court.

When there are public access rights involved as well as private access issues Herenga ā Nuku can help. Our help involves providing information such as geospatial mapping and technical knowledge. We have expertise in helping people negotiate enduring agreements about land.