Te mauri o te whenua and land access

Ngā hikoi no mua

Hundreds of years ago, tangata whenua arrived in Aotearoa and immediately began walking. Māori traversed, settled and named tracks, trails, mountains, valleys, waterways and settlements throughout the land.

- Te Waka ā Maui – Maui’s canoe, the South Island

- Te Ika ā Maui – Maui’s fish, the North Island

- Te Punga ā Maui – Maui’s anchor stone, Stewart Island

- Ngā Poito i Ruia e Taramainuku — the floats of the net cast out by Taramainuku, the offshore islands.

During this era of exploration, the connection between tangata and Papatūānuku became paramount. Survival and sustenance were different than in the much more luxurious Pacific islands. Throughout Aotearoa, Māori left place names that keep alive these ancient adventures.

These place names preserve whakapapa and support the mauri of the whenua. This mauri can never be moved — it connects the past to the future. Importantly for Herenga ā Nuku, this mauri draws from the walking adventures and experiences of tangata whenua.

Māori of Aotearoa are the only Polynesian people within the wider Pacific Islands families who predominantly focus on Tāne Mahuta rather than Tangaroa.

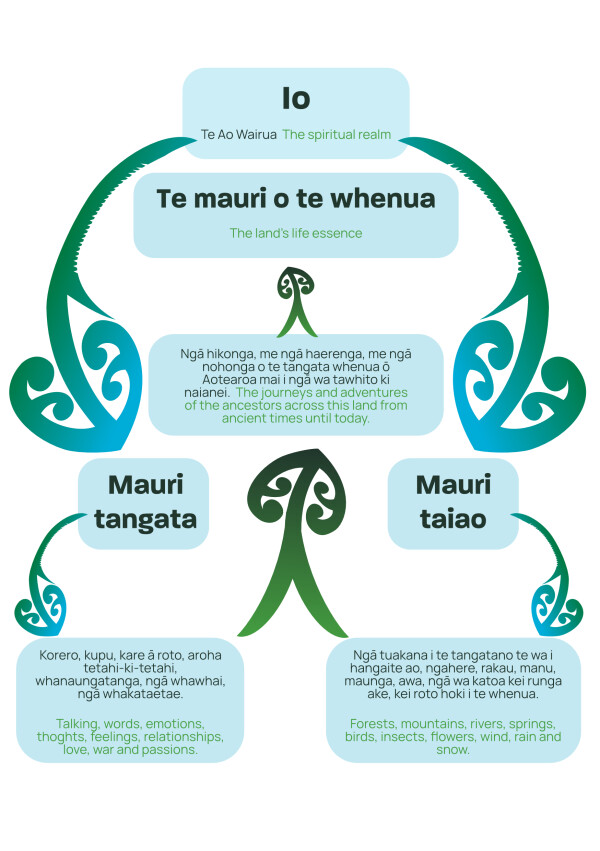

Herenga ā Nuku recognises the mauri of Aotearoa's land and forests. Te mauri o te whenua underpins all relationships with tangata whenua. It authenticates our cultural integrity across all relationships with tangata whenua. Recognising it means, rather than being driven by obligation, we, as an organisation, express ourselves with an ever-increasing knowledge of te Ao Māori.

Te mauri o te whenua is our anchor stone and reference point of cultural depth for all our work with tangata whenua, mana whenua and all our partners in the outdoor recreational sectors of Aotearoa.

Ngā waewaekaikapua – Māori adventurers

The whakapapa and pakiwaitara (legends, stories) of hapū and whanau are numerous. We see these in stories of love, wars, feats, endeavours and adventures. And all these stories are about walking. Tangata whenua are the original walkers and adventurers of Aotearoa.

The connections between hapū and whanau today draw from these stories and hīkoi of the past.

The extensive loss of forested lands means traditional outdoor access for tangata whenua has drastically declined. However, remnants and modern versions of old walking practices have survived and evolved. These include modern forms of hunting, rongoa expeditions, forest health projects, commercial forestry and the traditional connections that Māori still retain to wāhi tapu. Māori also participate in western-style recreation, such as hiking and biking.

Herenga ā Nuku recognises tangata whenua as the original walkers of Aotearoa. We intend to infuse this recognition into all our public access projects, tools, products, and partnerships.

Mana whenua – Māori lands today

Mana whenua has several meanings. Primarily, it refers to the tribal domain and range of a hapū. It also incorporates the spiritual, cultural, and ancestral elements of land and people.

People often use the term mana whenua to refer to land legally owned by Māori. While this is accurate, this definition should not supersede the primary meaning of mana whenua (domain, jurisdiction, and range).

A further traditional perspective of mana whenua covers all of Aotearoa. This system of tribal domains centres on the approximate tribal boundaries that existed before the era of land confiscation by the Crown.

Approximately 6% of Aotearoa is in legal Māori ownership. Most of this remnant Māori land is rural and remote, and, in many cases, it is near publicly accessible lands and reserves.

In 2020, after being approached by a local trails group, Gisborne Cycle and Walkway Trust (GCWT), we initiated community korero and hui about a regional tracks strategy — Tapuwae Tairāwhiti. We agreed to take a tikanga-based approach to the strategy. We are working with hapū and iwi interested in developing ancestral trails in the region. They want to rebuild cultural connections to sites of enduring significance — such as the headwaters of tupuna awa. We now have a memorandum of understanding that provides for mana whenua to have strategic oversight over Tapuwae Tairāwhiti. The project enables cultural access and storytelling as part of its work to build connections between communities.

For Herenga ā Nuku’s work, mana whenua, land is divided into four categories. Each category presents different scenarios, challenges, and opportunities for providing free and enduring public access while simultaneously supporting tangata whenua land aspirations. The four categories of Māori influence on land are ture whenua, Te Tiriti Settlement land, mana whenua, and urban Māori mana.

1. Ture whenua land

Ture whenua land includes Māori freehold, customary land, Māori reserve land and court-held land. Ture whenua land is the largest portion of land legally owned by Māori. Ture whenua land is made up of agriculture, forestry and horticulture and regenerating land. It doesn’t include general private land that Māori own.

Ture whenua lands are those that Māori retained through colonisation or received as compensation for other land taken by the Crown. Ture whenua land precedes Te Tiriti o Waitangi settlements and is administered via Te Ture Whenua Māori Act 1993. There are approximately 8000 ture whenua land blocks. These blocks represent about 4% (1,300,000 hectares) of the land originally owned by Māori. Groups of related whanau typically own these remnant land blocks. However, the actual configuration of owners can vary extensively from one block to another. This is because the Crown sought to reduce the number of Māori landowners and to amalgamate blocks to create larger farms.

Due to historical Land Court actions, the role of mana whenua, and connections to land has sometimes shifted. In many cases, ahuwhenua landowners are closely related whanau, but in other situations, the Māori Land Court has merged much more loosely related whanau groups. In some extreme cases, ahuwhenua trust land is located well outside of the traditional tribal area of the owners. This occurred during an era of compensatory land swapping when Māori were given land outside their region in exchange for prime lands taken by the Crown.

A single ture whenua block can easily have 500 owners, with some exceeding 2000. Thousands more people whakapapa to these blocks but no longer have a legal shareholding.

A slight majority of ture whenua land is actively managed. Most of this is for sheep and beef farming. There are also dairy and forestry blocks and an increasing amount of horticulture.

Just under half of ture whenua lands are currently classed as under-utilised. However these blocks often provide ecological benefits through regenerating forests.

In both cases, it is typical for neighbouring farmers or recreationists to use Māori land of this type informally. These blocks often connect and contribute to neighbouring publicly accessible lands and reserves.

The proximity of ture whenua lands to public tracks and trails is common, and, in many instances, ture whenua lands are part of a wider network of public access tracks.

Herenga ā Nuku is committed to recognising and supporting ture whenua Māori land governors, particularly where opportunities to connect and partner exist. We will explore Māori-led projects to improve enduring public access within or relative to these lands.

2. Te Tiriti Settlement land

Te Tiriti Settlement land refers to land returned to tribal or pan-tribal groups via the Te Tiriti o Waitangi settlement process. Te Tiriti settlement lands represent the interests of much larger groupings, usually iwi. Te Tiriti settlement land typically includes Crown forests, reserves, and lakebeds. Two examples of extensive forests returned to settlement entities are Urewera National Park and Kaingaroa Forest.

Each Tiriti settlement land has its own legislation and customised legal status.

Although Te Tiriti settlement land is a much smaller overall area than ture whenua land, it is relevant to outdoor public access. Most settlement land contains public access requirements as a condition of the settlement.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi influences Herenga ā Nuku more widely than just land-related work. Te Tiriti guides our tangata whenua relationships by driving our responsibility as a Crown agent to understand rangatiratanga and mana motuhake and to apply comprehensive kāwanatanga subject to tikanga. Te Tiriti also endorses mana whenua and is intrinsic to all Crown relationships with Māori, whether they are Tiriti settlement-based or not. Herenga ā Nuku will lead among government agencies by advancing beyond an ‘obligations’ paradigm and infusing Te Tiriti into all aspects of our strategic relationships.

We work with Tiriti settlement governance entities, supporting their specific settlement clauses that may involve private ownership rights or public access clauses. We support mana whenua with their initiatives to preserve and enhance public access or limited access to settlement lands. We endorse mana whenua leadership of this public access.

Herenga ā Nuku is committed to upholding, honouring and giving practical effect to Te Tiriti for the betterment of all types of land access in Aotearoa.

3. Mana whenua land

The term mana whenua has multiple meanings. The Crown often uses the term to refer to a particular group of Māori who hold mana in the form of legal ownership over the land — Te Tiriti settlement land or ahuwhenua land.

However, mana whenua more accurately also describes the original territorial domain of a particular hapū or whanau. Hapū still hold mana over their original tribal lands even though much of those lands are no longer in their legal ownership. A further complexity with the term mana whenua is that it can refer to the mana of the land itself, as opposed to the mana of the people who relate to the land.

These variations in meaning often create confusion and subsequent miscommunication between agencies and tangata whenua.

Typically, Māori will primarily use the term mana whenua to refer to tribal domains and secondarily use it to refer to lands legally in Māori ownership. Conversely, government agencies sometimes only use the term to refer to legally-owned land while minimising or ignoring the concept of mana over a more extensive tribal domain. Herenga ā Nuku is aware of and integrates both concepts of mana whenua into its work.

We support the relationship that Māori as tangata whenua have with land that extends beyond legal ownership.

Herenga ā Nuku worked closely with Ngāti Hikairo to reroute a section of Te Araroa that passed through the sacred Te Porere Redoubt near National Park. Te Araroa walkers had been crossing a historic reserve and passing immediately adjacent to the upper redoubt on privately owned land. The upper redoubt has an urupā in which the Māori pa defenders, who lost their lives in the last major battle of the NZ Wars, are buried. There is no obvious boundary between the private land and the reserve, and for all walkers and visitors, the private land would appear as part of the reserve. Ngāti Hikairo and we put a new route around the redoubt site, diverting walkers around the urupā. We also added new signage, maps and track notes.

4. Urban Māori mana whenua

Urban Māori mana whenua is a subset of mana whenua. Where there is a significant concentration of urban Māori, that population exerts a type of mana whenua over the area, sometimes centred around an urban marae or other significant feature.

Many Māori do not live in their original tribal regions. Urban Māori sit on a spectrum of ‘connectedness’ to their tribal areas, ranging from a holistic, unbroken connection (ahi kā) to complete disconnection. Sometimes, a person can be ahi kā on one side of one’s ancestry and disconnected on another.

Urban Māori communities have unique outdoor access characteristics, challenges and opportunities. Urban marae and other areas in cities (usually private land or urban reserves) have evolved into a version of mauri whenua and mana whenua.

From a land area perspective, the term urban Māori can apply to localities, suburbs and even entire townships.

Herenga ā Nuku recognises the need to understand better and engage urban Māori communities regarding outdoor access patterns and aspirations.

Toi tū ngā whenua

Each of the four categories of Māori influence on land also influences the creation and support of enduring public access to land. These issues include:

- ownership complexities (multiple ownership, traditional ownership)

- generational challenges regarding land management

- government influence on land use decisions

- support for public access (historical access, assumed access, allowed access, emerging access, partial access).

Herenga ā Nuku strives to support and connect with all Māori land types in an empathetic and respectful way. We aim to honour the history, mauri and the current reality for tangata whenua and mana whenua.

Note: Nga ara o ngā wai – waterways as pathways

Pathways over water are essential for tangata whenua and mana whenua. They seamlessly integrate with and cannot be separated from land-based paths. In many instances, water pathways were the primary route for tribal and whanau connection. This applies particularly to hapū near large rivers, lakes and coastal areas.

Ngā ara o ngā wai also relates to traditional Māori knowledge of ocean pathways, ocean currents and offshore islands. In recent years there has been a significant resurgence in the use of waterways for transport, recreation, and sport by tangata whenua and mana whenua.

Tangata whenua and Herenga ā Nuku

Herenga ā Nuku seeks to understand and work with tangata whenua. We hope that enduring relationships that benefit land and people will be the outcome. We believe we enhance or accelerate work to restore the environment and strengthen the oranga of people when we work with an in-depth connection to mauri, to wairua and to tangata.

Herenga ā Nuku seeks to understand and work with tangata whenua. We hope that enduring relationships that benefit land and people will be the outcome. We believe we enhance or accelerate work to restore the environment and strengthen the oranga of people when we work with an in-depth connection to mauri, to wairua and to tangata.

This is fundamental to understanding our shared interests and values concerning the environment and the lands over which tangata whenua have either legal ownership or traditional mana whenua. An effective partnership with tangata whenua is when:

- access to land does not impact its ownership,

- it protects and restores the land’s natural beauty, and

- it recognises sites of significance and all other features critical to the kaitiakitanga of tangata whenua.

We will prioritise early, appropriate, and transparent engagement and commit to supporting formal and informal opportunities to work with Māori.

We will encourage and support behaviour and activity consistent with achieving this framework’s intent and integrity.

We will work in a committed partnership with tangata whenua, individuals, whānau, hapū, communities and Māori organisations.

More information

The Whenua Māori Service at Te Puni Kōkiri – why whenua matters

Te Ara, The Encyclopedia of NZ – Papatūānuku: the land

Mehemea he pātai, he whakaaro rānei, ēmēra mai ki a Doug Macredie.