The interventions that improve walkability in rural towns

Pero Garlick is the latest JH Aspinall Scholar that Herenga ā Nuku Aotearoa has supported to undertake research at the University of Auckland. His study looked at ways to improve walkability in rural towns.

For the last 70 years, rural town have been designed to enable car traffic at the expense of pedestrians.

This is State Highway 54 in a residential area of Feilding. It has been designed with pedestrians as an afterthought, with legal places to cross 500m apart.

Zoning processes have segregated land uses and set buildings back from the street, and traffic planning has focused on moving car rather than people.

Planning for pedestrians is increasingly a priority for town planners, but this work often focuses on cities. Garlick argues that rural towns should be equally pedestrian friendly. He says small towns have the necessary conditions to be great walkable environments — they are physically small and have relatively low traffic volumes. Already, of rural residents travelling to work, 16% walk. This challenges the assumption that rural residents only drive.

“We could reimagine rural towns in New Zealand to centre the pedestrian and transform them into ‘15-minute’ neighbourhoods, where everything people need is within easy walking distance,” says Garlick.

There is little research that looks at walkability in rural towns. What little does exist is mainly from the USA, Canada and Australia and tends to focus on public health rather than planning and design.

Garlick’s research identifies five efficient and cost-effective interventions rural towns can implement to improve walkability.

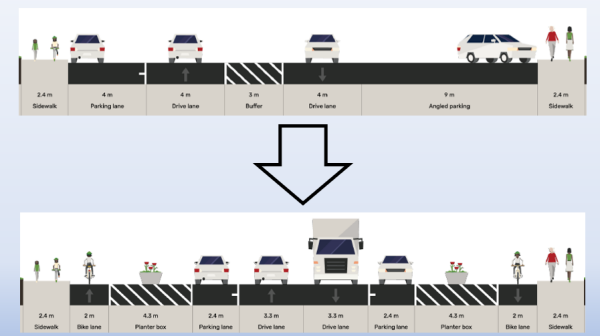

Intervention 1: Road diet

A road diet reallocates existing road space away from cars. It does this by narrowing the carriageway through a simple road restriping. This creates space for bike lanes, wider footpaths and parklets. This reduces traffic speed, improves safety and improves pedestrian amenities.

This intervention does not usually adversely impact traffic capacity and is affordable. However, many main streets in rural towns are also state highways helping traffic get through the town. In these instances, towns must collaborate with Waka Kotahi.

State Highway 6 in Winton is the town’s main street but is excessively wide. With 4m-wide travel lanes, a turning median and angled parking resulting in a total width of 24m. This is for a road that only carries 4,500 average daily trips. Highways acting as main streets do not lead to productive walkable towns.

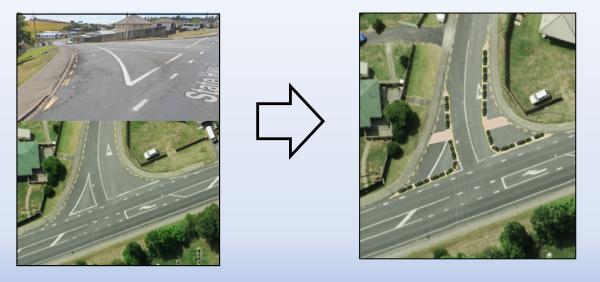

Intervention 2: Kerb extensions at intersections

Kerb extension is the umbrella term for traffic-calming measures that widen the footpath and narrow the roadway. Examples include mid-blocks, chicanes, bus bulbs, zebra crossings and reducing the corner radius at intersections. The objective is to slow traffic, improve pedestrian visibility to traffic and reduce crossing distances for pedestrians.

Kerb extensions are most effective at intersections. They can be affordable if councils employ tactical urbanism1.

These imagined interventions at the intersection of State Highway 3 and Harper Ave in Ōtorohanga reduce the width of the pedestrian crossing from 30m to 8m.

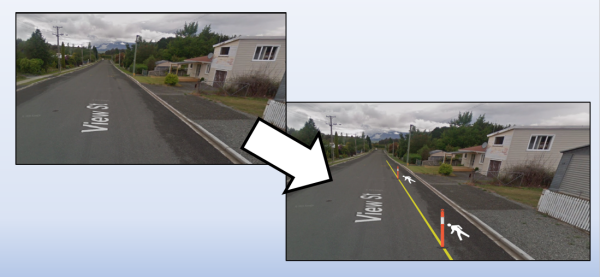

Intervention 3: Reallocating the road shoulder for pedestrians

Rural towns often have poor or no footpaths. The ideal solution would be to retrofit footpaths, but that is expensive. A cost-effective solution is to reallocate the road shoulder to a footpath through tactical urbanism. The safest way to do this is to physically separate cars and active transport users from each other. This intervention is only effective with adequate protection and enough room to reallocate road for walkers and cyclists. Many NZ roads do not have enough space.

View St in Manapouri only has a footpath on one side of the road. Using a road diet, part of the street can be reallocated to the pedestrian lane with plastic or concrete bollards separating pedestrians.

Intervention 4: Tactical urbanism to revitalise town centres

Rural town centres face challenges to be economically successful, vibrant and walkable. A successful low-cost strategy that addresses this challenge is tactical urbanism.

‘Create the Vibe’ in Thames closed off a side street adjoining the main road to turn it into a plaza. It attracted more people to the town centre and functioned as the ‘town square’.

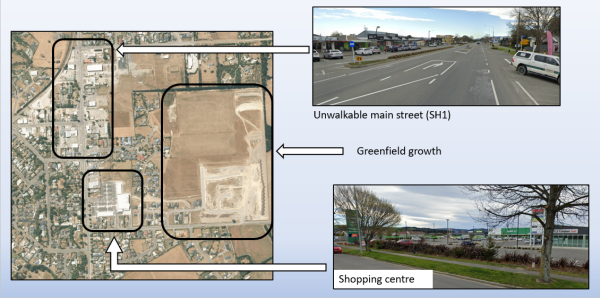

Intervention 5: Land use/zoning reform

Garlick’s final recommended intervention is land use or zoning reform. This has a long-term focus. A town’s land-use pattern is essential to its walkability, but it evolves with various stakeholders influencing it. Rural towns are often low-density and have separate land uses.

Changing the land-use regulations to accommodate small-scale infill and mixed-use land allows residents to live near daily destinations. It means businesses can thrive along a walkable main street.

Amberley has a poor land-use pattern and main street. It promotes new growth in car-centric greenfield developments, making the town less walkable. It could accommodate growth with infill development and use other interventions to improve its main street. Councils can incentivise subdivision provisions to support walking connections.

Conclusion

Garlick’s research calls for more funding and direction by central government to improve rural town walkability. He says tactical urbanism is a practical, affordable approach to start the work of improving walkability.

Garlick says rural district councils should keep growth in their communities compact and allow for mixed land use. He says Waka Kotahi should focus on providing local amenities when state highways go through rural towns rather than concentrating on through traffic. But community buy-in is essential for each of these walkability measures to achieve their goal.

Footnote

1Tactical urbanism is low-cost, temporary changes to towns that change the way people move around and engage with public space. People can implement these changes quickly using low-cost materials while councils plan bigger, more complicated infrastructure. They can overcome the intransigence of conventional planning — delivering immediate improvements to walking and cycling networks. Some examples include painted crossings, street-surface art, kerb extensions and planter-box protected cycleways.